CAT-COT-COG-DOG

One of the many things I love to spend time on is a good puzzle. Word puzzles are a ton of fun! In particular, word morphs can keep my attention for hours. A word morph is a puzzle game where you are given a starting word, and an ending word, and you change one letter of the word at a time to come up with the end word. The challenge is to get from one word to another in the fewest number of steps. Often the words are somehow linked, such as cat to dog, or help to safe. Maybe it is these puzzles that really draw me to training using shaping.

Shaping is the process in training where we start with the dog doing something and change that something into something else through successive approximations. What that means is each training step brings the dog closer and closer to the end behaviour. As an example, let me describe teaching a dog to approach without jumping up, as I did with a client’s dog last night. This dog, a young exuberant labrador loves to rush up to people, and throw herself at people. At about 30 kg, this dog is big enough to really hurt someone if she chooses the wrong person to jump upon. This is like the starting word.

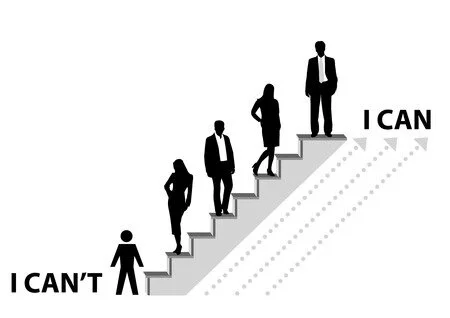

Training is a process of steps towards a goal. If you try and take too many steps at once, you will stumble and fall back down to the beginning. When you take the process of learning step by step by step, you go from can’t to can and success with your dog. Copyright: cristianbr / 123RF Stock Photo

The desired behaviour is to have her come up to me, and keep her feet on the floor while I touch her. In behaviour parlance, we would call this the target behaviour and I always like to break that behaviour down into the simplest terms possible. I don’t like to use more than 7 words to describe that behaviour because the more simply that I can describe it, the easier it is to find the steps to achieve my goal. Let’s call this behaviour “approach with 4 feet on the floor.” That is 6 words, so it fits my desire to have no more than 7 words to describe what I am training, but you will notice that it cuts out the touching part. By limiting myself to 7 words at most, I prevent myself from lumping too many things into one training session.

Now that I have the starting behaviour and the ending behaviour, the rest of the training session is a matter of inserting the intermediate steps. This part of shaping requires that I let go of the idea that I am going to run the entire training show without input from my training partner. It requires that I allow my learner to do what she wants without interference. During the training session she may do exactly what I don’t want, and for the purposes of this example I am just going to let her do that. I think that for some of my human students this is perhaps the hardest part of shaping. Most of my students whose dogs jump up are so deeply appalled by the undesired behaviour that when it happens they give the dog feedback that may or may not be helpful. Usually, the feedback they give the dog is just exactly something that will maintain or even strengthen the behaviour. Pushing the dog down may feel like a solution but in fact, teaches the dog that you are more than happy to play a vigorous wrestling game for instance and from the dog’s perspective, yelling is just noisy barking that humans do sometimes.

Here is how the session played out. We let the dog off leash in the training hall and she began to run around away from me. This is not an uncommon reaction when the dog is off leash, so the very first thing I did was to set the dog up so that she was unlikely to do the undesired behaviour. Setting up so that you get what you want is the hallmark of great training. After about three minutes, she approached me and her person, and I clicked my clicker and threw a treat behind her. I should mention that this dog understood what a clicker was and what it meant, so if you want to try this out, you should teach the dog that click means treat before you start.

When I clicked the clicker, the dog stopped dead in her tracks and stared at me. For her, this was probably the first time that she had received any feedback about approaching other than yelling or pushing! She was genuinely surprised at the outcome. I made sure she could see me throw the treat and she took off like a shot to chase the treat. Once she took the treat, she started to explore the training room again, sniffing the toys and finding dropped treats that had been left by previous trainers. It took her another two or three minutes to approach us and again she approached us at a run. I clicked again and threw another treat behind the dog. This time there was a short light bulb moment for the dog; approaching me was a safe, interesting thing to do, and it resulted in treats! From there the dog began to approach me right away after getting her treat. 7 clicks and treats later she was coming in towards us eagerly but under her own control. Throughout this time, I simply chatted with the client, never giving the dog directions, never micromanaging the dog, just clicking the dog for approaching, and throwing the treat away to get the dog to leave in order for me to set up a chance for the dog to return.

From that point forward, I wanted the dog to start to approach more closely while maintaining her self control. To get her to do this, I just delayed clicking until she approached more closely. About 10 more clicks and she was walking right up to me. I had a little bit of history with this dog, working with her on the down stay, so she made a quick leap of logic and without any prompting or cuing or other information from me, she approached me and lay down. I really liked that, so I clicked and threw several treats; I made approaching and lying down really, really valuable!

As I said at the beginning, shaping is a lot like a word morph game. In this case the steps were approach, approach and stop, approach under self control, approach more closely under self control, approach and lie down at my feet. You will notice that the learner added in something I had not planned for; lying down. If she had added in sit, or stand and make eye contact, that would have been fine with me too; in this case, it doesn’t matter to me what she did when she arrived as long as it wasn’t putting her feet on me. In five steps, I achieved my goal of “approach with four feet on the floor”.

This is what my goal behaviour looks like for the labrador retriever I was working with. Knowing what I want is an important part of shaping. If I don’t know where I am going, it is going to be much harder to take steps towards that goal. It is important to be able to form the goal behaviour in terms of what I do want, not just what I don’t want. Copyright: lightpoet / 123RF Stock Photo

In order to get my goal of being able to touch this dog, I would have continued to train, clicking and treating for approaching and lying down while I first stepped towards the dog, and then stepping in and reaching but not touching, then stepping in and touching her and finally stepping in, reaching, touching and stroking her. The important thing to notice in this case is that once the dog is doing what I want her to do, I am shaping the activity that happens around her while she is doing the behaviour that I want. This is an important next step in most training; trainers might call this proofing. What we mean is for the dog to continue to do the target behaviour no matter what else happens around them.

It is popular to only define shaping in terms of reinforcement training but in fact, shaping can happen in any of the four training quadrants; you can certainly use punishment to shape behaviour too. With this very same dog we did this to keep her safe after she jumped up on a treat station and broke it. We have small flower pots on the wall to hold treats, and like many dogs before her, she tried to jump up and use her claws to pull the pots off the wall. She broke a pot and it would be dangerous to her to continue to do this, so we didn’t want her to do that. When she jumped up on the wall near the pots, we called out “that’s enough”. If she stopped right away, we would toss treats for her to clean up. If she continued to the pot, we would call out “too bad” and then quietly and calmly catch her and put her in the classroom crate for a few minutes. Then we would let her out to try again. In this way, the dog learned that jumping up on the wall near the pots was a behaviour that would predict an outcome that she didn’t like very much. It wasn’t stressful for her, it was just something she didn’t like.

It took about five repetitions to teach the dog not to jump on the walls, but that was really only the first step; we really wanted this dog to stop fixating on the pots altogether, so the next step on this shaping protocol was to call out the warning as she approached the wall. This time she learned the game even more quickly; it took her three repetitions to decide that approaching the wall near the pot was not a desired behaviour. From there, almost half an hour passed before she tried the behaviour again. In this way, we had shaped the behaviour we wanted using a negative punishment protocol.

Shaping can work with extinction too. We use extinction to teach dogs not to snatch treats until they are told. Extinction is the process of doing nothing at all until the behaviour changes and then reinforce the lack of the behaviour. At first, we ask only that they not touch our hand when a treat is extended towards the dog. Then we require that they stay off the treat for a second. Then two seconds. Then three, five, seven, ten and so on until the dog learns that trying to get at the treat just won’t work. We essentially teach the dog to stop trying to get the treat for longer and longer periods of time.

The important thing to understand about morphing behaviours like changing words is to make changes slowly. If you want your dog to pay attention to you when there are other dogs in the vicinity, then don’t start in the middle of the dog park; start far away, and pay your dog for giving you his attention at whatever distance he is already successful. Some dogs struggle so much with attending to me out of doors that I start out with just hand feeding outside my front door. Then I take them to places in the car and just feed them in new places. In general, if I have a really distracted dog, I want them to take treats nicely in ten places before I start asking them to do anything at all in a new place. Then I start asking for things they will do at home on my front step or in the driveway. From there, I take them in the car and ask them to get out of the car and do something really easy. Each time, I pay really well for whatever the dog does what I ask. Just as teaching the dog a new skill requires that I increase the difficulty of the skill in a step wise manner, so does working in a new environment.

Just like changing words one letter at a time, shaping or morphing behaviours is a lot of fun. One of the biggest reasons it is a lot of fun is that if you are only changing a little bit at a time, you are going to be fairly successful in very short order. It is a lot less fun when you try and change more than one thing at a time. When you are training, if you are not succeeding, ask yourself if you are changing too much too fast and if you are, slow down and enjoy the success.